Attention returns to decisions on UPC opt-out

January 2017

Introduction

The UK Government announced on 28 November that it will ratify the Unified Patent Court (UPC) Agreement, in spite of the prospect of Brexit in 2019. As a result, the UK Intellectual Property Office is currently understood to be working to a timetable in which orders of ratification for the UPC Agreement (and the Protocol on Privileges and Immunities) will be presented to Parliament for approval in February or March 2017, leading to ratification of both instruments shortly afterwards. Providing Germany ratifies; a 'sunrise' period of the UPC can then follow. Parties can begin to opt-out European patents from the UPC system during this period. The UPC Preparatory Committee is currently aiming for the sunrise period to begin in September 2017, with the full opening of the court in December 2017, although this may change.

The UPC is therefore back on track, following uncertainty caused by the Brexit decision of 23 June, and attention is now returning to the important question of whether patentees allow some, or all, of their European patents to become automatically (there is no 'opt-in') subject to the jurisdiction of the UPC; or, whether they wish to opt them out. When addressing this question, there are three aspect to opt-out that need to be addressed: what opt-out does, the procedure for opting-out and, its strategic implications. This article provides an overview of these aspects.

What opt-out does

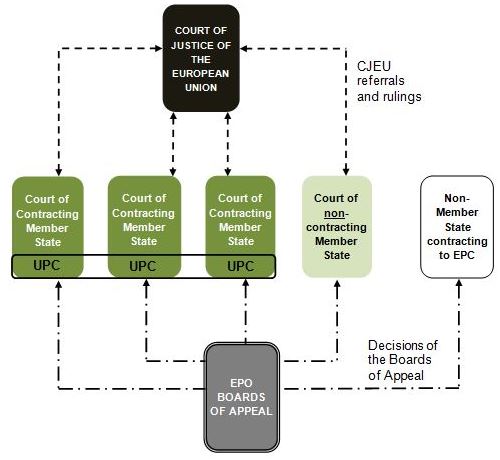

To understand opt-out and the associated transitional period, it is first necessary to look at the place that the UPC will take in the European patent system as a whole. This is because the UPC will not exist in isolation, but side-by-side with the existing national courts. In particular, as Figure 1 shows, the national courts will fall into three categories, depending on their relationship with the UPC and the European Union (EU):

- national courts of the 25 EU Member States (in which we include the UK) contracted to the UPC ('Contracting Member States') (shown schematically by three dark green boxes);

- courts of the three EU Member States that have not signed the UPC – Spain, Poland and Croatia (represented schematically by one light green box); and

- thirdly, national courts of the countries that are signatories to the European Patent Convention ('EPC') but cannot join the UPC because they are not EU Member States (represented by one white box).

Figure 1. The place of the UPC in the European court system (appeal court not shown)

Unlike the other courts shown, the third type of court cannot refer matters to the Court of Justice (black box). But all courts will, to a greater or lesser extent, take notice of decisions of the Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office (dark grey box). For simplicity, the UPC Court of Appeal and the national appeal courts are not shown in Figure 1.

The UPC itself, although most easily thought of as a separate jurisdiction of its own, is actually a court of each and every Contracting Member State simultaneously. This is represented in Figure 1 by a box in black outline which overlays the courts of the Contracting Member States. Opt-out and the transitional period are concerned with the inter-relationship between the UPC and the Contracting Member States' courts only.

Which patents can be litigated where?

When the UPC comes into force, it will also be possible to request that newly granted European patents become 'European patents having unitary effect' (referred to as 'Unitary Patents'). This means there will be three types of patent available in Europe, under the new system:

- Unitary Patents;

- European patents; and

- national patents.

Which of these patents can be litigated in which type of court in the new system?

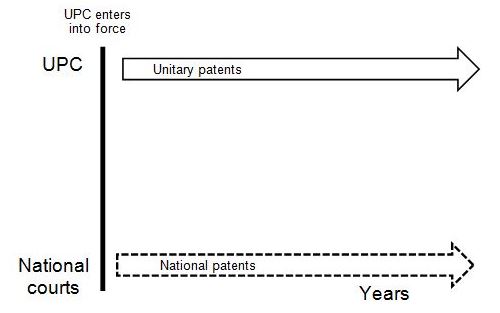

Disputes concerning national patents will continue to be heard only in the national courts – this will not change in the new system. In contrast, Unitary Patents will only be actionable in the UPC, as regards matters within the UPC's 'exclusive' competence. This includes the key areas of revocation, enforcement (including injunctions) and non-infringement declarations. These two jurisdictions are represented in Figure 2. Here, the arrow at the top of the figure illustrates Unitary Patent actions taking place exclusively in the UPC over time. The broken-outline arrow at the bottom of Figure 2 shows national patent actions taking place exclusively in the national courts over time.

Figure 2. Jurisdiction for Unitary and national patents in the new system.

By contrast to national patents and Unitary Patents, the jurisdiction in which European patent disputes are heard is determined by the rules on opt-out and the transitional period.

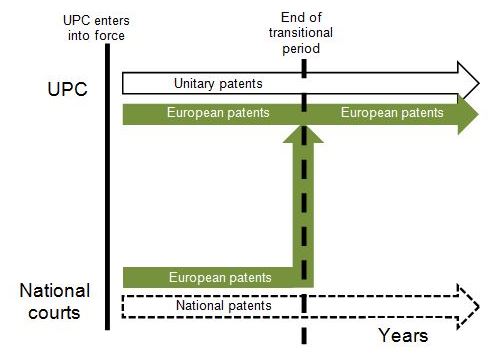

The transitional period: the effect of opt-out

All European patents will eventually be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the UPC. However, a period of adjustment – a transitional period – will operate first, in which patentees have some control over whether their patents are subject to potential actions in the UPC. This period will initially last for 7 years, although it may later be extended by a further seven years. Figure 3 develops the picture of jurisdiction over time shown in Figure 2 by adding European patents. During the seven-year transitional period, European patents can be litigated in either the UPC forum (top, dark green arrow) or the national courts of their designation (bottom, dark green arrow). However, once the transitional period has expired (shown by the vertical dotted line) all disputes about matters within the UPC's exclusive competence concerning European patents must be started in the UPC and the UPC only. Actions already started in a national court must continue in the national court. Furthermore, during the seven year transitional period, the proprietor (or applicant) for a European patent may opt-out that patent from the exclusive competence of the UPC. However, if an action relating to the patent has already been filed in the UPC, the opt-out is barred. There is also a right to withdraw an opt-out (discussed below).

Figure 3. Jurisdiction for European patent actions during and after the transitional period.

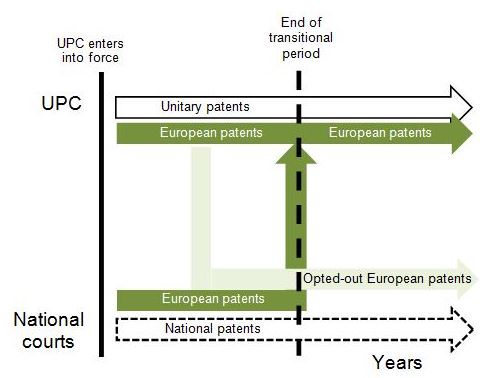

The effect of opt-out is to remove the choice of the UPC as a jurisdiction for European patents during the transitional period and for the rest of the life of the patent, together with any SPC based on it. This is shown in Figure 4. In Figure 4, the light green arrow shows the effect of the opt-out on the jurisdiction in which a European patent must be litigated. On the left-hand side of the figure, the light green arrow descends from the UPC jurisdiction down to the national court jurisdiction, indicating that the opted-out patent can now only be litigated in the national court of its designation. In Figure 4, the opt-out is shown schematically as taking place halfway through the transitional period, but it could be exercised at any time from the first day of the court’s operation up until the expiry of the transitional period. After expiry of the transitional period, the opportunity to opt-out is lost.

Figure 4. The effect of opt-out on the jurisdiction of a European patent action.

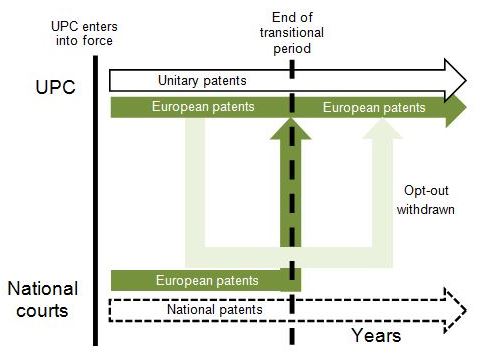

The transitional period: the effect of withdrawal of opt-out

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of withdrawal of the opt-out. Withdrawal takes the European patent concerned out of the exclusive jurisdiction of the national court of its designation and back within the dual competence of the UPC and national courts (if withdrawn prior to the expiry of the transitional period) or within the exclusive competence of the UPC (if withdrawn after the end of the transitional period). An opt-out can be withdrawn at ‘any time’: before or after the transitional period expires and at any time during the life of the patent or that of an SPC based upon it. However, there is an important restriction on the ability to exercise the withdrawal: if a European patent is already the subject of litigation in a national court the withdrawal of the opt-out is not permitted. Such litigation must continue in the national court. The opt-out cannot be withdrawn even after such litigation has concluded.

Figure 5. The effect of withdrawal of opt-out on the jurisdiction of a European patent action.

Opt-out: what happens to SPCs?

Opt-out automatically extends to an SPC that is based on an opted-out ‘basic patent in force’. After a European patent has already expired, the opt-out of the SPCs based on it is still achieved by opting-out the expired patent. SPCs are not currently available based on Unitary Patents, although the European Commission is considering how this might be achieved. However, if and when such SPCs become possible (either as unitary rights or an adaptation of current national rights, or both) it will not be possible for them to be opted-out of the UPC.

How opt-out is achieved

Opt-out procedure

In order to exercise the opt-out of a European patent or application from the exclusive competence of the UPC, together with any SPC granted on the basis of it, an Application must be lodged with the UPC Registry. The Application must contain the details of the patent, plus any SPC that is granted on the basis of it, or the patent application in question. These details include the numbers and designated states of the patents. The name of the proprietors or applicants for the patent (and the holders of any SPC) must also be included, together with their postal and electronic addresses. There is no fee payable. If all the above requirements are satisfied, the opt-out will be effective from the date that it is entered in the Register.

The sunrise period

A 'provisional operation period' for the UPC will commence prior to the opening of the court. In addition to allowing certain steps to be taken in preparation for the court to enter fully into force, during this period a sunrise period will begin in which it is possible to record opt-outs of European patents in the UPC Registry. The sunrise period therefore provides the opportunity for a proprietor to keep European patents subject to the jurisdictions of the countries in which they are designated, before a third party is able to lodge a revocation action centrally in the UPC.

The UPC Preparatory Committee is currently aiming for the court to come into full operation in December 2017. The Committee also suggests that the sunrise period could come into effect as early as September 2017.

Whose decision is it to opt-out?

An Application to opt-out must be made in the name of the proprietor of a granted patent, or the applicant for a patent application. A proprietor of a European patent is taken to be the person registered or entitled to be registered as a proprietor in the national register. A declaration of proprietorship is necessary in the absence of an up-to-date record of the proprietor in the relevant national register of a granted patent, or the EPO register in respect of applications. If the granted patent or application is owned by two or more proprietors all the proprietors must lodge the Application jointly. The consequence of this is that joint owners must all agree that a European patent is to be opted-out, or the Application cannot be made.

The Application to opt-out must be made in respect of all of the Contracting Member States for which the European patent is designated. This means that should the ownership of one or more designations have been assigned to a third party after grant, those third party proprietors must also be party to the Application to opt-out. However, European patent designations for countries that are not Contracting Member States are not affected by the opt-out.

As regards SPCs, if an SPC has been assigned so that the owner of the SPC and the proprietor of the patent upon which it is based are no longer the same, the proprietor and the SPC owner must lodge the opt-out Application together. Again, cooperation will be needed between these parties to ensure an opt-out in these circumstances.

A proprietor is the person registered or entitled to be registered as the proprietor in the national register, under national law. This would not normally include an exclusive licensee. Consequently, an exclusive licensee who wants a say in the opt-out of the patent to which they have rights, particularly if they are the party that is likely to be enforcing it, should negotiate an obligation on the proprietor to obtain their agreement to opt-out and withdrawal in the terms of the licence.

Strategic considerations – why opt-out and why not?

Given that there is a right to opt-out of the UPC, should proprietors of European patents use it? This is of course a strategic question, which requires careful consideration of the consequences of opt-out for all European patents in a portfolio. There are a number of issues to bear in mind. The most significant of these is discussed below:

Revocation and injunction

A successful revocation action, or revocation counterclaim to an infringement action, will have effect in all Contracting Member States that have ratified the UPC system. At the time the court comes into operation, this may not be all 25 Contracting Member States. However, as more countries ratify the UPC Agreement, the scope of the effect of UPC decisions will become accordingly greater. Likewise, for infringement actions (including preliminary injunctions), enforcement decisions may not be effective in all Contracting Member States in the early operating life of the UPC. However, even given these limitations in the early stages of the UPC’s operation, their scope is extensive compared to the current system of national court decisions, which are limited to national territories. In particular, decisions will cover the significant commercial markets of Germany, France and the UK from the outset, because the ratification of these countries is mandatory before the UPC can begin. Furthermore, in the months after the UPC comes into force, the scope of application of decisions can be expected to grow to include most, if not all, of the Contracting Member States, as they ratify. As a consequence, the powerful enforcement opportunities in the UPC have to be balanced with the risk of simultaneous revocation in a large number of countries.

Fees and costs

A UPC action may in some cases be bifurcated between infringement and revocation and, despite a number of consolidation provisions, there will be circumstances in which patentees have to enforce the same patent in separate proceedings against different defendants. Nonetheless, an action in the UPC, either to enforce a patent or to revoke one, prevents the need for parallel actions between the same parties in the national courts. Consequently, the potential cost of a UPC action must be weighed against not only the court fees that might be payable in several national courts, but also the costs of paying the legal teams running and managing the parallel national actions. For European patent families covering several commercially very significant countries, the benefits in time and cost of using the UPC may be obvious. For other patents the cost benefits alone may not be so clear.

Market signals

Some patentees may wish to adopt a ‘safety first’ approach in which they opt-out their most commercial important patents, removing them from the risk of a pan-European revocation, until the court has become established and more is known about the approach it will take to patent validity. However, such a strategy may need to be managed carefully in the future, to ensure that it does not send the wrong signals to competitors about the proprietor's confidence in the strength of the patents being opted-out.

Losing pan-European enforcement

Patentees should be wary of assuming that the downside of a potential pan-European revocation can simply be avoided by opting-out a European patent early, with the intention of withdrawing the opt-out when it becomes desirable to use the upside of pan-European enforcement. This is because, as noted above, if a revocation action or non-infringement action is started in respect of an opted-out patent in a national court, that action must remain in that court and a withdrawal of the opt-out is barred, whether the action has concluded or not – the pan-European enforcement power is lost for good and the patentee will find that it is unable to enforce in the UPC when it really wants to.

Other factors

There are other factors that, while they are unlikely to sway a decision on opt-out on their own, should be considered: in some cases there will be differences between UPC law and national law – the Bolar exemption is narrower in the UPC than many national laws, for example; there is uncertainty about the approach the new court will take to enforcement and revocation; and, patentees will want to be involved in the UPC in order to 'shape' how law and procedure develops in the court.

In summary

The greatest risks and benefits of litigating in the UPC are pan-European revocation or pan-European enforcement, respectively. It is these that are most likely to drive decisions about whether patents should be opted-out or allowed to remain in the UPC. The potential costs savings of litigating in the UPC will also have an impact on these decisions. Therefore, whether a portfolio is small or large, decisions on most European patents will need to be made according to the strength and commercial value of the patent concerned. This will take time and thought. Although the UPC Preparatory Committee is currently aiming to open the court for business in December 2017, the sunrise period, during which proprietors may begin to register opt-outs, will start before this. Although these dates are provisional and may change, as they have before, the decision on what, or what not, to opt-out is now being brough back into focus.

If you have any questions on this article or would like to propose a subject to be addressed by Synapse please contact us.

Paul England

Paul is a senior associate and professional support lawyer in the Patents group based in our London office.

"To understand opt-out, it is first necessary to look at the place that the UPC will take in the general European patent system as a whole."

"The sunrise period provides the opportunity for a proprietor to opt-out a patent before a third party is able to lodge an action for revocation."