A changing industry and changing rights

October 2015

In the first part of a two part extract from the forthcoming Globe Law & Business title "Intellectual Property in the Life Sciences", Paul England discusses how intellectual property rights attempt to adapt to a changing life sciences industry.

There are arguably three major forces that are shaping the development of intellectual property law in the life sciences at the moment: the diversification of pharmaceutical businesses into new areas of innovation; the advance of technology; and the increasingly global reach of those businesses. Diversification has come in the context of the challenging economic circumstances of the ‘Great Recession’, greater pressure on drug pipelines due to the stringencies of regulation and the costs of R&D, increasing generic competition and patent expiry. Indeed, in respect of the latter, estimates have abounded in recent years on the loss of sales expected to result from the expiry of patents protecting blockbuster drugs1. The march of technology has driven innovation in areas little imagined before the sequencing of the human genome, such as the impact of advanced DNA sequencing and bioinformatics methods on personalised medicine. As a result, these continue to be times of great challenge for the life sciences sector and the traditional, small-molecule blockbuster business model may soon prove to be just one of a number of other sustainable possibilities.

However, there is one thing that is likely to remain a constant through this diversification. It applies to businesses from university start-ups to the established pharmaceutical giants - the need for market exclusivity. Without it, the costs of research into new drugs could never be financed:

"It is the patent system, which has made the advances in medicines possible. Although economists sometimes debate whether the patent system is useful generally, no one has ever seriously challenged its place for medicines. And that is because it is so obvious that without a reliable patent monopoly there is simply no incentive to invest. The entire period of the command economy of the Soviet Union did not produce, so far as I know, any major pharmaceutical product. And in the West, even in those rare cases of an important invention being made at a University (eg the cephalosporin antibiotics) or by a small inventor or company (eg the anti-epilepsy drug sodium valproate), it has been the pharmaceutical industry which has undertaken the risk of the considerable costs of development."2

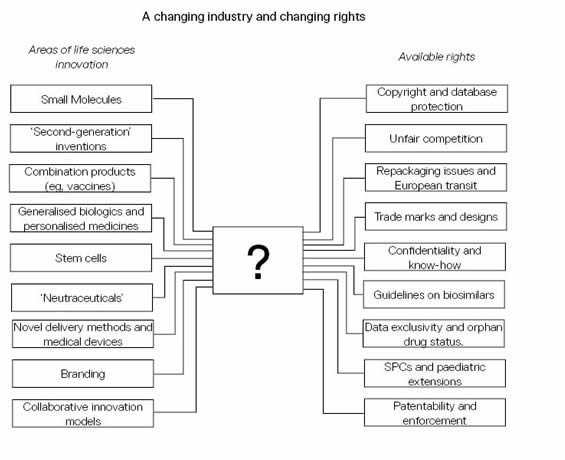

This is where the protection of intellectual property rights - whether they are traditional patents and trade marks, or relatively new forms of protection such as supplementary protection certificates (SPCs) – is important because, with every new direction that technology takes, there is a need for intellectual property laws to keep up. However, the pace at which technology develops is much faster than that of the law (and the ability to enforce it) and this is often found lagging behind. Combined with diversification, this is now a big challenge for the life sciences industry, the legislator and the intellectual property practitioner alike. As Figure 1 shows, there are many types of products now emerging from the life sciences industry (left-hand column), but do the rights available (right-hand column) adequately protect them?

Take for instance SPCs. The SPC regime works well for a product consisting of a novel and single active ingredient that is covered by a patent and a first marketing authorisation. However, the healthcare sector has increased in complexity since the original SPC legislation was introduced in 19933 and the current regime struggles to cater for this. The problem is acute for combination drugs, such as vaccines, and a raft of references has been made to the Court of Justice of the European Union asking for the correct interpretation of the SPC Regulations on a number of questions that arise for such products; arguably, stretching the SPC Regulation beyond the limits for which it was originally conceived.

Consider, also, the development of computer-assisted methods for analysing genetic data – bioinformatics – mentioned above. These 'in-silico' methods increasingly rival traditional 'wet-lab' techniques for the identification of genetic markers of disease. Such is the speed at which an individual's DNA can be sequenced and screened that this technology opens up the possibility of finding the root causes of disease in specific groups rather than addressing merely the symptoms of whole populations (so-called personalised medicine). But can these innovations and the drugs that result from them be protected? First, there is the issue of whether patents should be allowed for isolated forms of naturally occurring DNA molecules. This question remains a live issue in the United States. In the United Kingdom too, a related issue required the attention of the Supreme Court in Eli Lilly & Company v Human Genome Sciences Inc4. This concerned how much information a patent for a gene and the protein it expresses must disclose about its therapeutic application to satisfy the requirements of industrial applicability. The issue arose because the link between a disease and a sequence is based on in-silico comparative screening methods of DNA sequences, where therapeutic application is inferred from DNA sequence homology with genes of known function, rather than traditional wet-lab techniques in which the therapeutic protein and its application are known, or demonstrated, to some extent from the beginning.

What about protection for the DNA sequence and other data that is the basis of these discoveries? European database right has so far proved narrow in application although cases in the bioinformatics context have not yet come before the Court of Justice of the European Union. Similarly, the extent to which data copyright may afford protection remains speculative.

It would also be a mistake to assume that the important intellectual property rights applicable to life sciences are confined to patents and attendant means of protection such as SPCs. Other rights are also of tremendous importance, particularly trade marks. This is evident from the way these rights have been the focus of parallel importation disputes over the years. However, there is a growing realisation, in the light of the pressures being brought about by patent expiry, that branding and design of the drugs themselves, their packaging, and/or their delivery methods are important in their own right as means to distinguish the products of innovators from their generic rivals, build brand loyalty and even provide market exclusivity – take for instance, AstraZeneca's 'Purple Pill' and Pfizer's 'Little Blue Pill' for Viagra. Trade marks, trade dress, passing off, unfair competition and rights protecting designs are therefore essential rights in the portfolio of the life sciences company.

Figure: Can all innovations be protected by one or more intellectual property rights?

The globalisation of life sciences and intellectual property law

What is the relevance of pharma's global reach, in this context? The global marketplace in which business now operates is a familiar aspect of today's world, but it poses special challenges for intellectual property lawyers and their commercial partners working in life sciences. This is because intellectual property rights are typically national in scope. Their protection therefore ends at the borders where they are registered. But even if rights are registered in every country for which protection is needed, and even though some rights require no registration at all to subsist, there is a another difficulty - the often significant disparity between the protection available between one country and another, either because some rights simply do not have an equivalent in all countries or because those equivalent rights are interpreted by national courts in differing ways. How is the life sciences industry to operate internationally under all of these different regimes? This remains an issue as between European countries, between Europe and the United States and between the United States and Canada, never mind fast-growing markets such as those of India and China.

But, again, the law is catching up - slowly - to recognise that trade is increasingly borderless. This is most apparent in Europe. Although the European bloc remains a highly fractured system, pan-European instruments, such as the European Patent Convention, and EU laws governing marketing authorisations, supplementary protection certificates, border enforcement and biotechnology inventions, seek to create uniformity. The Community Trade Mark is the exemplar of this, being a unitary right that covers all member states of the European Union. There is also the subject of medical device regulation which, although it does not concern market exclusivity, is becoming an increasingly important hurdle that must be cleared for many products in the life sciences.

The European Union is not the only area where common rules apply. There is also the Eurasian bloc of nine states that are signatories to the Eurasian Patent Treaty, currently: Russian Federation, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Moldova, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The Eurasian Patent Office was set up as a common channel through which to grant equivalent patents protecting the countries within this vast geographical territory. There are similar groupings in the Gulf and Africa.

Then there are of course the treaties that lay down rules for the establishment and treatment of intellectual property on a cross-continental scope. Globalisation is nothing new in this respect, with international rules going back to the 1880s. However, it was not until the recent TRIPS agreement that the global harmonisation of rules for the obtaining and enforcement of intellectual property has been driven forward on a truly international basis.

The second part of this article “The challenge of true IP harmonisation” will appear in the November 2015 edition of Synapse.

This article is an extract from the forthcoming Globe Law & Business title "Intellectual Property in the Life Sciences", published in November 2015.

If you have any questions on this article or would like to propose a subject to be addressed by Synapse please contact us.

1 See, for example, EvaluatePharma®, World Preview 2016, dated May 2010.

2 The Right Honourable Sir Robin Jacob, “Patents and Pharmaceuticals” - a paper given on November 29 2008 at the presentation of the Directorate General of Competition’s Preliminary Report of the Pharma-sector inquiry.

3 Council Regulation (EEC) No 1768/92 which came into force on January 2 1993, now replaced by Regulation (EC) No 469/2009 of May 6 2009 (the ‘SPC Regulation’).

4 [2010] EWCA Civ 33; Supreme Court judgment of November 2 2011.

Paul England

Paul discusses how intellectual property rights are adapting to a changing life sciences industry.

"There are arguably three major forces that are shaping the development of intellectual property law in the life sciences at the moment…"

"The pace at which technology develops is much faster than that of the law."