Patentability of parthenogenic stem cells questioned

Summary and impact

June 2013

Another reference has been made to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) for a preliminary ruling on the patentability of stem cells, under Directive 98/44/ED (the "Biotechnology Directive"). The case is called International Stem Cell Corporation ("ISCC") v Comptroller General of Patents1. The question referred concerns whether stem cells obtained from parthenogenetically stimulated human ova are excluded from patentability as "human embryos".

The reference follows an earlier ruling by the CJEU in its Brüstle decision (C-34/10)2 that stem cells obtained from human embryos directly, or indirectly, are unpatentable and its application in the German Supreme Court.

However, the technology used by ISCC uses parthenogenetic activation of oocytes and so does not involve the destruction of a fertilised ovum capable of developing into a human being. For this reason it is seen as a more ethical alternative to the technology at issue in Brüstle.

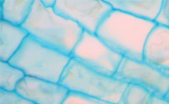

ISCC seeks two patents for a technology that produces stem cell lines, and corneal tissue specifically, from the parthenogenetic activation of an unfertilised ovum. It was common ground between ISCC and the Comptroller that such parthenogenetically-activated ova do not produce totipotent stem cells, but instead pluripotent cells, and are therefore not capable of developing into a human being.

ISCC seeks two patents for a technology that produces stem cell lines, and corneal tissue specifically, from the parthenogenetic activation of an unfertilised ovum. It was common ground between ISCC and the Comptroller that such parthenogenetically-activated ova do not produce totipotent stem cells, but instead pluripotent cells, and are therefore not capable of developing into a human being.

Despite this, at first instance the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) followed Brüstle and held that even parthenogenetically created stem cells are capable of commencing the process of development of a human being, and therefore they use human embryos for commercial purposes and so are not patentable.

In coming to this decision, the UKIPO considered and applied the CJEU ruling in Brüstle. In this case, the CJEU which decided that as soon as a human ovum is fertilised, it becomes an embryo because it commences the process of development of a human being. However, in relation to unfertilised parthenogenetically-activated ova, the CJEU appeared to have proceeded on the assumption that such an ovum can proceed to term (or intended that it was only necessary to commence the process of development and not necessarily to complete it). It held that the classification of "human embryo":

"must also apply to a non-fertilised human ovum into which the cell nucleus from a mature human cell has been transplanted and a non-fertilised human ovum whose division and further development have been stimulated by parthenogenesis. Although those organisms have not, strictly speaking, been the object of fertilisation, due to the effect of the technique used to obtain them they are, as is apparent from the written observation presented to the Court, capable of commencing the process of development of a human being just as an embryo created by fertilisation of an ovum can do so."

ISCC argues that the CJEU is incorrect as a matter of scientific fact and that its ruling on Brüstle's technology does not apply to include parthenogenetically-activated ova. On the contrary, ISCC argued that it was acte clair that parthenogenetically activated stem cells were not excluded from patentability.

In particular, ISCC focused on the reasoning in the CJEU's above statement that to be a human embryo it was necessary to be "capable of commencing the process of development of a human being which leads to a human being". ISCC argued amongst other things, that, in context, the Brüstle decision only excluded parthenotes insofar as they were capable of producing totipotent cells.

The Comptroller, however, argued that the CJEU's judgment could also be read as excluding parthenotes from patentability even if they were ultimately incapable of producing a human being. The Comptroller therefore submitted that the test was not clear and that a further reference to the CJEU was necessary.

Consequently, on appeal from the UKIPO the Patents Court has referred the issue to the CJEU. The judge hearing the case, Henry Carr QC, nonetheless expressed his view that if the process of development is incapable of leading to a human being, then it should not be excluded from patentability as a "human embryo". The question referred is as follows:

Consequently, on appeal from the UKIPO the Patents Court has referred the issue to the CJEU. The judge hearing the case, Henry Carr QC, nonetheless expressed his view that if the process of development is incapable of leading to a human being, then it should not be excluded from patentability as a "human embryo". The question referred is as follows:

Are unfertilised human ova whose division and further development have been stimulated by parthenogenesis, and which, in contrast to fertilised ova, contain only pluripotent cells and are incapable of developing into human beings, included in the term "human embryos" in Article 6(2)(c) of [the Biotechnology Directive]?

The CJEU ruling in this case is going to be very important for those hoping to develop and invest in similar stem cell therapies commercially. However, even in the event of a negative ruling for ISCC from the CJEU, other technologies for making stem cells are available that claim not to involve the destruction of a human embryo and should, therefore, fall outside the scope of the CJEU ruling in Brüstle. These include cells taken for preimplantation genetic diagnosis ("PGD cells") and induced pluripotent stem cells ("iPS cells").

See a September 2014 update to this article.

If you have any questions on this article or would like to propose a subject to be addressed by Synapse please contact us.

Dr Matthew

Royle

Matthew is a senior associate in the Intellectual Property department based in our London office.

Dr Paul

England

Paul is a senior associate and professional support lawyer in the Patents group based in our London office.

"The judge hearing the case expressed his view that if the process of development is incapable of leading to a human being, then it should not be excluded from patentability as a ‘human embryo’."