Brexit – no end in sight

With just under four months to go until Article 50 notification expires and the UK is set to leave the EU, even the most outlandish predictions are becoming entirely plausible as Theresa May faces the seemingly impossible task of selling her 'deal'. Of the many possible developments in the next year, certainty is the one thing most likely to elude us.

Trying to write an article predicting what will happen next in the Brexit saga is difficult at the best of times, but particularly so in this period of frenetic activity. There is a good chance that much of this article will have a very short shelf life indeed. But then again, it may not. In one of our earliest Brexit articles, written before the Referendum, we discussed what Brexit might look like – would it really happen? Would it be hard or soft? Would we stay in the Single Market or not? Would we stay in the Customs Union? What would happen to the Irish border? Worryingly (although arguably predictably), we are not much wiser today. As we have been repeatedly told, nothing is agreed until everything is agreed. So where are we?

The Withdrawal Agreement

The EU27 approved a Withdrawal Agreement on 25 November 2018. While it has been technically agreed by the UK, it must now be approved by Parliament. The EU says this is the best deal we can get, so what's on the table?

We don’t claim to have read the entire agreement but some of the key (and most controversial) aspects of the agreement are as follows:

The transition period and a possible extension

The transition period is intended to last from 30 March 2019, to 31 December 2020. During this time, the UK and EU will use their "best endeavours" to reach a future trade agreement. If they fail to do so, the transition period may be extended once for up to two years with joint agreement. This is one the major issues for the hard Brexiters. An extension would mean the UK stays in the Single Market (preserving freedom of movement) and the Customs Union, contributes to the EU budget, and continues to apply EU law (apart from specified provisions, including parts of the Common Agricultural Policy).

Irish border

This has been the most contentious element of the negotiations. There are now two options as to what happens if, at the end of the initial transition period, there is no trade agreement which prevents a hard border on the island of Ireland. Either the transition period could be extended as set out above, or the Irish backstop solution will be applied. Under the backstop, a single customs territory between the EU and the UK will apply "unless and until a subsequent agreement becomes applicable". This would apply to all goods except fisheries and would require level playing field commitments to ensure fair competition. There would be dynamic alignment on state aid, the UK would be required to implement three EU tax Directives, and non-regression clauses would prevent the UK from introducing lower standards than exist currently on social, environmental, and labour regulation.

While the backstop would be intended to apply temporarily until superseded by a future relationship agreement which would avoid a hard Irish border, there is no stipulated end to the backstop and the UK would only be able to withdraw with the agreement of the EU. Again, the hard Brexiters say it is unacceptable that the UK would not be able to withdraw unilaterally from a UK-EU customs arrangement and would not be free to pursue third party trade deals while in it. The backstop would also require Northern Ireland to align with EU Single Market rules and would involve non-customs checks between Great Britain and Northern Ireland on some types of goods. This is a major issue for the DUP which does not want Northern Ireland treated differently from the rest of the UK.

Role of the Court of Justice of the European Union

The CJEU will have jurisdiction in respect of proceedings or preliminary rulings brought before the end of the transition period. The CJEU will also consider any alleged breaches by the UK of treaty or transition periods which may be referred up to four years after the end of transition. Jurisdiction also falls to the CJEU in the event of failure by the UK to comply with an administrative decision of an EU institution for the same four year period. The UK may intervene and participate before the CJEU in the same way as a Member State until all judgments, orders, proceedings and requests for preliminary rulings of the type referred to in the Withdrawal Agreement have been concluded.

Dispute resolution in relation to Withdrawal Agreement

A Joint Committee will be set up to resolve any disputes relating to procedures set out in the Withdrawal Agreement. If the Joint Committee fails to resolve the issue within three months, the matter may be referred to international arbitration. Before the end of the transition period, the Joint Committee will set up an arbitration panel consisting of ten EU and ten UK members and another five to be jointly proposed. Members from this panel will be appointed to settle disputes in accordance with the Withdrawal Agreement procedures. Disputes will need to be settled within 12 months or a referral of six months where urgent. Where the dispute relates to the interpretation of a concept or provision of EU law, the arbitration panel may request a ruling from the CJEU which will be binding on the parties.

The Political Declaration

Alongside the Withdrawal Agreement sits the Political Declaration setting out the Framework for the Future Relationship between the EU and the UK. Unlike the Withdrawal Agreement, the Political Declaration is not intended to be a legally binding agreement but is a statement of intent.

It is hard to draw any real conclusions from the Political Declaration and to a large extent, it has been drafted to prevent just that in order to try and include something for everyone. It is as though the government hopes that each person will put their own spin on it. There is a lot of talk of closeness, going above and beyond WTO rules, and bespoke arrangements, but all of that is conditional on the degree of alignment with the EU which the UK is prepared to accept, and on the preservation of a "level playing field" in terms of competition.

For the hardline Brexiters, there is a reference to the end of freedom of movement, and a statement of "determination" to resolve the Irish border issue, the UK's sovereignty is stressed and it is recognised that the UK will form its own trade policy. On the other hand, the indivisibility of the EU's four freedoms and the Single Market are repeatedly emphasised and there is no reference to "frictionless trade". Another red flag for hardliners, is the wording on tariffs for goods: "ambitious customs arrangements that…build and improve on the single customs territory provided for in the Withdrawal Agreement". This has led Brexiters to fear a permanent customs union. Finally, the CJEU is envisaged to have a limited role in relation to disputes involving EU law.

Much political capital has been made from the fact that the document is a mere 26 pages long and is undeniably vague, however, there is no real surprise here. The EU27 have always insisted they cannot begin negotiations on the future relationship until the UK has left the EU. All the Political Declaration does (and all it was ever going to do) is postpone the big decisions and underline that uncertainty will continue.

The government's 'next steps' wishlist

- The House of Commons passes a resolution approving the Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration.

- An Act of Parliament is passed which provides for the implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement

- The European Parliament gives consent to the draft Withdrawal Agreement by simple majority after which the Council of the European Union concludes it on behalf of the EU by qualified majority.

- The Withdrawal Agreement is legally binding on the parties. The UK leaves the EU on 29 March 2019, transition and future relationship discussions begin.

Can the deal go through?

Under the terms of the UK's EU Withdrawal Act 2018, (not the same as the Withdrawal Agreement), both the Withdrawal Agreement and the Political Declaration have to be approved by Parliament and a vote is set to take place in the House of Commons on 11 December after five days of debate.

The government needs 320 votes to get the deal through and currently looks to have between 230 and 250. It is extraordinary to watch politicians on opposite ends of the Brexit spectrum unite in their disapproval of this agreement for very different reasons. Theresa May has clearly done her utmost to produce a deal which stays in a Brexit middle ground but it seems that she has displeased far more more than she has appeased. With Labour, the DUP, the SNP and the Lib Dems set to vote against the deal, along with a large number of Tory rebels (estimates vary but at the time of writing, are between 80 and 90), the deal currently looks set to be rejected, even accounting for around 15 or so Labour rebels likely to support it.

These figures may yet change. The number of Tory rebels may reduce with the threat of a general election or turmoil in the markets. There may be more Labour MPs than predicted who will vote in favour of the deal to please their 'Leave' constituents. May is framing the choice to Leavers as: 'this deal, no deal, no Brexit', and to Remainers as 'this deal or no deal/hard Brexit'. The starker options may eventually become sufficiently unpalatable to enough MPs for the deal to sneak through, but that seems unlikely, at least at the first time of asking.

If the House of Commons rejects the Agreement and Declaration on 11 December, the government must make a statement about how it intends to proceed within 21 days. The plan will then be debated in Parliament on a motion in neutral terms although the motion can, potentially, be amended. Very few people seem clear on what exactly happens at this point and the extent to which the neutral motion can be amended. The government claims hardly at all (which does beg the question as to how this vote can be meaningful), but others argue that it is within the gift of the Speaker John Bercow to decide how far the amendment can go. We may be about to see some very arcane parliamentary procedures come to light.

New legislation will be needed if the deal is definitively rejected (there can be more than one time of asking) to prevent the UK leaving the EU without a deal. Of course, this legislation would only deal with the UK side – the EU would also need to take action to prevent a no deal, most probably by voting to extend Article 50.

Is there a plan B?

There has been much talk recently about a 'Norway plus' solution in the event that the current deal is rejected by Parliament. Depending on who is being asked, this could be membership of EFTA or the EEA and EFTA, but what it probably means is EFTA, the EEA plus at least a temporary customs union. The Withdrawal Agreement would be accepted as is, but the Political Agreement would be amended to set out a path to EFTA and, possibly also the EEA.

The surprise is that this is being touted both by Brexiters (who see it as a short-term solution while a trade agreement is negotiated, despite the fact that the EFTA countries and the EU have indicated they would not permit this), and by soft Brexiters and Remainers, who see it as a long-term solution and the 'least bad Brexit'. Norway plus would probably be more palatable to many Labour MPs, and to the DUP as there would be no need for a hard border. The SNP has also expressed support for EEA membership as the closest thing to staying in the EU.

It is, however, hard to see how this arrangement would deliver for the committed Brexiters as it would not end freedom of movement (although there is limited scope for a temporary exemption where migration is causing real economic hardship) and it would commit the UK to accepting relevant EU laws it had no say in making, not to mention requiring ongoing EU budget payments. As this is very much an emerging option at the moment, it's difficult to say what, if anything, the government might eventually propose along these lines; Theresa May certainly appears to have ruled it out, at least for now.

What next?

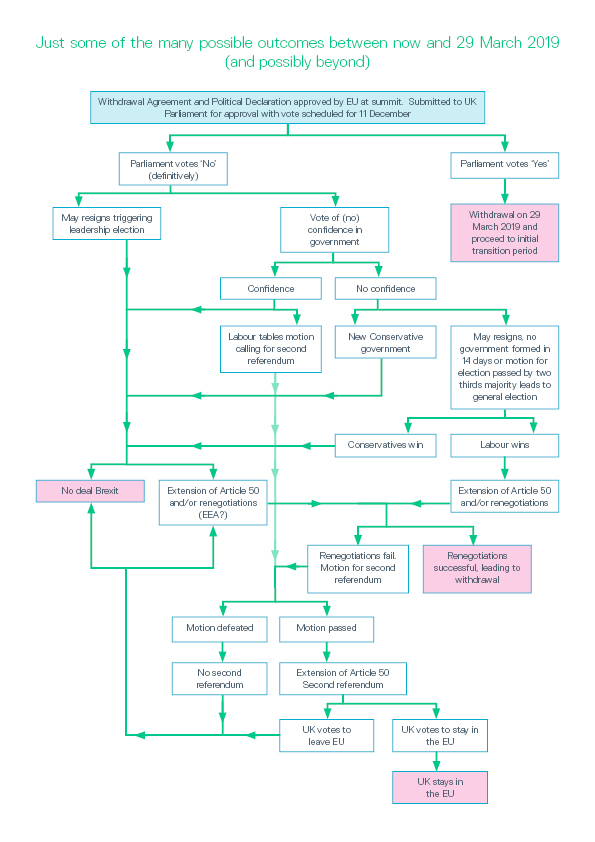

There are so many permutations of possible outcomes and the paths to them, it's almost impossible to represent them all but we've had a go at showing some of the main ones. It's worth underlining that these are by no means exhaustive. They do not deal with repeat motions or events, the legal wrangling that might interrupt progress, or with a possible change in Labour leadership.

More importantly, it is not just up to us (unless the CJEU decides we can unilaterally withdraw Article 50 in what would be the height of irony). If the Withdrawal Agreement is not approved, then any extension or suspension of Article 50 must be agreed unanimously by the EU27 as well as by the UK. The EU has signalled it is unprepared to renegotiate but it is also likely that it would agree to extend Article 50 if a major event like a general election or a second referendum were to take place. It is worth remembering that nobody (outside the hardest of hard Brexiters) thinks no deal is a viable option.

A mountain range of cliff edges

With all the talk of a 'deal', it is easy to assume that all we need is a single agreement to be concluded by 29 March 2019. In fact, the Withdrawal Agreement which the EU27 signed up to on 25 November, is just the first step in the process. Even if the Withdrawal Agreement passes through Parliament by 29 March 2019, we are more or less guaranteed to have a 'blind Brexit' in terms of a future relationship which could take years to negotiate, far beyond any potential transition period.

If the Withdrawal Agreement is signed and agreed by the EU27, the European Parliament and the British Parliament, the EC will then produce a discussion paper outlining the basis on which negotiations for an ongoing relationship would proceed. These negotiations would then have to result in a full agreement. The draft Withdrawal Agreement runs to over 500 pages and that's the simplest piece of the puzzle! Despite Liam Fox's assertions that a trade agreement with the EU would be the "easiest in history", it seems inconceivable that one could be completed during a 21 month transition period – not least because it will involve not only negotiations with the EU as a whole, but also, in practice, with each Member State. This means that even if we avoid a cliff edge in March, there will be another one looming at the end of any initial and any extended transition period. No deal is an option at almost every turn, particularly if you take 'deal' to mean the future trading relationship, rather than the mechanism of withdrawal.

The readiness is all

We do not think we are sticking our necks out when we say that the UK will be negotiating with the EU, whether on withdrawal or a future relationship, throughout 2019 and for the foreseeable future unless a second referendum reverses the results of the first, although even that would involve a fair amount of negotiation.

If we fall off the March cliff edge or if the Withdrawal Agreement is approved by Parliament, that will bring a degree of clarity (albeit with a great deal of initial confusion in a no deal scenario). In either case, it will be the future relationship negotiations that will be absolutely crucial, and these will go on until at least the end of the transition period in December 2020 (if there is one), and most likely well beyond. Whether or not we have the added excitement of a change in Tory leadership, and/or a general election and/or even another referendum, well, as usual when it comes to Brexit, we will just have to wait and see.

None of that is helpful to businesses which are treading a fine and exhausting line between preparing for the many options and not investing too heavily in an outcome which may never materialise. At some point, there will be clarity, but it's hard to see when; to quote the famously indecisive Hamlet (somewhat out of context): "If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come – the readiness is all."

If you have any questions on this article please contact us.

"It is hard to draw any real conclusions from the Political Declaration and to a large extent, it has been drafted to prevent just that in order to try and include something for everyone."